Water is Life: Re-Placing the Sacrament of Baptism (Ched Myers)

Water is Life:

Re-Placing the Sacrament of Baptism

“I went down to the river to pray, studyin’ about that good Old Way...”

The biblical story begins (Gen 1:2) and ends (Rev 22) in a “waterworld.” Here is a primal scriptural expression of a basic ecological truth: water is the single most important component in both the birth and continuation of life. It is, we might say, the Alpha and Omega of Creation—and thus deserves more careful attention than it has received in our churches.

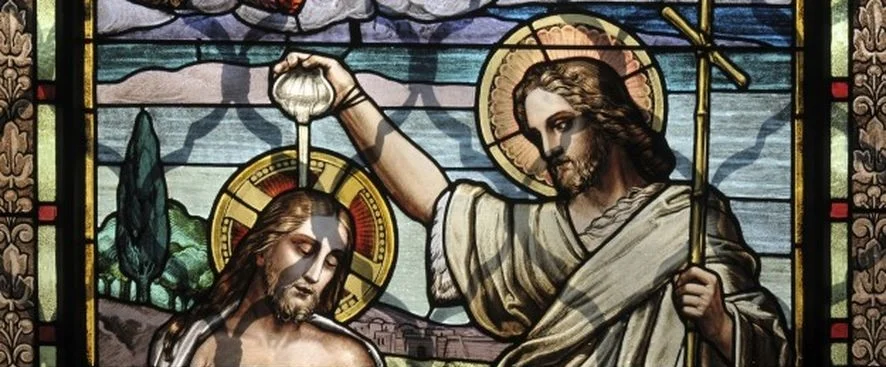

The ancient Christian ritual of baptism similarly articulates the ecological fact that without water there can be no life. We speak of baptismal waters symbolizing renewal—a metaphor predicated upon a deep biblical tradition concerning “living waters.” Today, however, Christians can no longer responsibly invoke this venerable tradition without also acknowledging the systematic dehydration of the earth by industrial civilization.

Deepening and interlocking environmental crises stalk our history, including climate destruction, species extinction, and declining natural fertility. Among these, one of the most pressing is “peak water.” Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute describes this as the critical point, already reached in many areas of the world, where we have overtaxed the planet’s ability to absorb the consequences of our water use. Its global symptoms include widespread desertification, water insecurity, declining water quality, water apartheid, and the drift toward international water wars. If present trends continue, it is estimated that 1.8 billion people will be living with absolute water scarcity by 2025, and two thirds of the world population could be subject to water stress.

These grim specters represents the dark opposite of baptism, portending only death, “signs of our time” that illuminate the old gospel imperative to “turn around” as an historic ultimatum. Yet water is the resource we in the First World arguably take most for granted—a privileged and cruel conceit that must change. A re-placed practice of baptism, however, can be a way of re-centering the church’s faith and mission around “watershed discipleship” as a matter of social justice, ecological sustainability and theological renewal.

In Mark’s baptism narrative (1:9–12) we find an interesting anomaly. Those coming out to John are baptized in the Jordan (Gk en); Jesus, however, is baptized into the river (Gk eis ton Iordanēn), a prepositional distinction with theological and social significance. While theologians usually understand Jesus’ baptism as divine empowerment “from above,” we could just as well argue he was being en-spirited from “below” through a deep submersion into his beloved homeland, grounding him in the storied Jordan watershed of his ancestors through which Creator still speaks. Being initiated into the sacred, wild spaces of a land groaning under Roman imperialism prepared Jesus for his campaign to liberate and heal his people and place.

Baptism is the only remaining universal sacrament across the ecumenical spectrum of our churches; how might it be re-placed? To be sure, the theology and liturgical practices of baptism remain largely domesticated in our churches, with infant baptism often reduced to a feel-good cultural ceremony. Yet the ancient litany calls on us to “renounce Satan and all his works, and sin, so as to live in the freedom of the children of God.” Cannot this sobering language be understood in terms of our struggle with the demonic personal and political pathologies that have brought us to the crisis of the Anthropocene, and the call to “repent”—which is to say, to turn around our dysfunctional history?

What would it mean to experiment with the old Anabaptist practice of “re-baptizing” believers--into their watersheds? Such a ritual would re-affirm the traditional discipleship notion of committing to the Way of Jesus, while also challenging church members to shed placelessness and immerse themselves, as did Jesus, into the holy waters of what Brock Dolman calls their “Basin of Relations.” Christians would thus recover baptism as a triple sign of covenant commitment: to Creator, to a people and to with that part of Creation in which we live and witness.

We ought at least break our ecclesial captivity to indoor sprinkling rituals, and recover baptism as an outdoor sacrament. Re-placing this rite back out in the watershed forces us to exercise literacy regarding our watercourses. We first have to locate a suitable local stream, pond or beach, which can be something of a challenge, especially for urban dwellers. Then we must confront the realities of degraded waters that are often unfit for human immersion—thereby becoming motivated in the process to organize for the restoration of those waters to health. Conversely, if for mobility (or weather) reasons it is impossible to move baptism outside, we can bring local waters into the sanctuary. Indeed, gathering such waters can be part of both the ritual and the pedagogy. The churchly practice of baptism thus compels us to become engaged with, and advocates for, watershed repair. This is one important way in which the church’s symbolic and civic life can be re-connected.

Re-placing baptism can help us see how local congregations are ideally situated to become centers for learning to know and love our places enough to defend and restore them. But we must first reinhabit our watersheds as church, allowing the natural and social landscapes to shape our sacramental life, mission engagements, and material habits. Developing a watershed ecclesiology simply involves consciously rethinking our collective habits. Creative representations of a watershed map (quilted or collaged, painted or sculpted) are particularly important to display prominently in the sanctuary, since we are trying to learn its design even as we wean ourselves off the abstractions of political cartography. Medieval cathedrals were full of iconography that functioned to teach the illiterate about the sacred traditions; given our ecological illiteracy today, such prompting and pedagogy is equally necessary. How can our music and litanies, altars and albs, furniture and flowers, liturgy and architecture help (and prod) parishioners to learn about this place where the body of Christ is incarnated?

In our work we have developed “watershed discipleship” as a frame, which is resonating among many faith rooted activists. The phrase is an intentional triple entendre:

1. It recognizes that we are in a watershed historical moment of crisis, which demands that environmental and social justice and sustainability be integral to everything we do as Christians and as citizen inhabitants of specific places.

2. It acknowledges the bioregional locus of an incarnational following of Jesus: our discipleship and the life of the local church inescapably take place in a watershed context.

3. It also implies that we need to be disciples of our watersheds: to learn them to know them in order to love them in order to save them.

Interestingly, ecoBuddhist poet Gary Snyder draws on the venerable Johannine language of baptism to describe the kind of deep conversion required if we Settlers are to reinhabit our bioregions today: “For the non-Native American to become at home on this continent, he or she must be born again in this hemisphere, on this continent, properly called Turtle Island.”

Understanding Christian discipleship fundamentally in terms of a commitment to heal the world by restoring the social and ecological health of our watersheds is a contextual, practical, and constructive approach to faith and practice. Re-placed ecclesial communities could make a crucial contribution to the wider struggle to reverse the catastrophe of the Anthropocene—and in the process recover the soul of our tradition. Christianity is deeply culpable in the present crisis, but also offers ancient resources for the deep shifts needed. It may require as many generations to reclaim our sense of rootedness in place in North America as it did to destroy it. But what is clear is we have no alternative. Re-placing is a great place to start.

###

Ched Myers’ most recent book is Watershed Discipleship: Reinhabiting Bioregional Faith and Practice (Cascade, 2016). Read more about Ched here. Most of his publications can be found at ChedMyers.org and watersheddiscipleship.org.