The Story of Haydn's Creation

Reprinted from Classical-Music.com. Here are some excerpts.

It was Haydn's encounter with Handel's oratorios in London that sowed the seeds of his most famous and enduring masterpiece: The Creation.

The structure of The Creation has an ideal simplicity and strength.

The libretto was finished some time towards the end of 1796, by which time Haydn had already begun to sketch the visionary 'Representation of Chaos'. Never one to hold back, Swieten annotated the manuscript he prepared for Haydn with suggestions for musical setting - a fugue here, descriptive tone-painting there - some of which were adopted, others rejected by the composer. He was, though, adamant that the words 'Let there be Light' - 'And there was Light' should only be said once, thereby claiming a small share in one of the most elemental inspirations in all music.

In the first two parts the six days of creation are announced in 'dry' recitative by one of the three archangels, Raphael, Uriel and Gabriel; after each act of creation the archangels expatiate on its wonders in accompanied recitative and aria; and each day after the first (which ends with the chorus heralding the 'new created world') culminates in a jubilant hymn of praise by the heavenly hosts.

Part Three, depicting the first morning in Eden, Adam and Eve's praise of all creation and their mutual love, falls into two sections that similarly climax in a triumphant chorus. In the arias and accompanied recitatives Haydn reveals his genius for instrumental tone-painting, using techniques honed in his operas and his Italian oratorio of 1775, Il ritorno di Tobia, but with a new boldness and sophistication - above all in the wonderfully inventive treatment of the wind instruments. The climactic choruses - the epitome of what the 18th century termed 'the sublime' in music - deploy Haydn's ripest symphonic and contrapuntal mastery with a freedom, variety and sheer brilliance of effect that were obviously inspired by Handel's example.

Its theological content, minimising conflict, guilt and retribution, also chimed in with Haydn's own personal faith - 'not of the gloomy, always suffering sort, but rather cheerful and reconciled', as an early biographer put it. Indeed, in composing the oratorio he felt he was performing an act of religious devotion. It is ironic, then, that the Catholic church was quick to take offence at its non-moralistic tone and alleged 'secularity' of expression, and banned it from places of worship.

The end result was the greatest triumph of Haydn’s career.

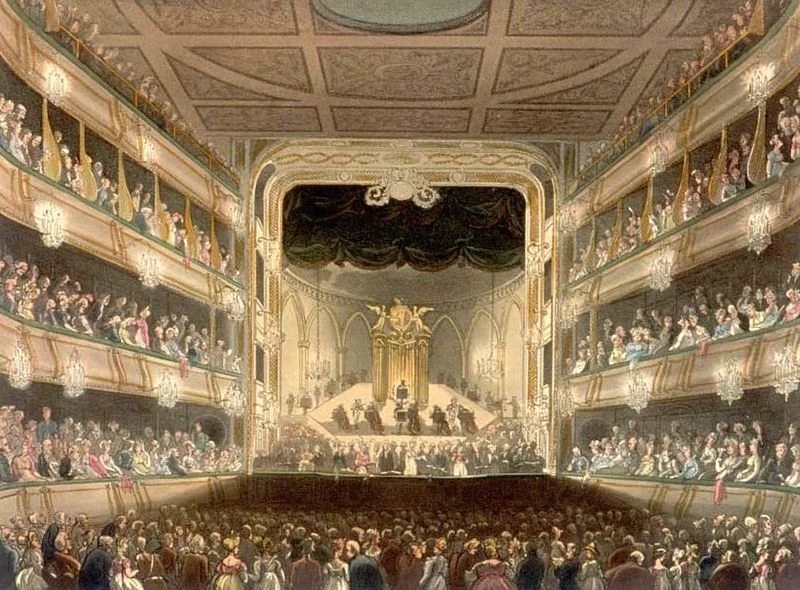

The Creation became a regular feature of the Viennese musical scene. Within a few years it was being performed throughout the German-speaking lands, in Britain (the London premiere took place on 28 March 1800) and in France. With its effortless fusion of the popular and the ‘sublime’, the innocent and the sophisticated, the oratorio appealed to Kenner – connoisseurs – and Liebhaber – amateurs – alike. Rarely before or since has a musical masterpiece been so perfectly attuned to the spirit of the age.

Replying to a letter expressing admiration for The Creation, Haydn wrote in 1802 that ‘Often, when I was struggling with all kinds of obstacles... a secret voice whispered to me: “There are so few happy and contented people in this world; sorrow and grief follow them everywhere; perhaps your labour will become a source from which the careworn... will for a while derive peace and refreshment.”’ These words are typical of a devout, humble yet by no means naive man.

Haydn’s hopes were richly fulfilled in his lifetime. In our own sceptical and precarious age we can still delight, perhaps with a touch of nostalgia, in Haydn’s unsullied optimism, expressed in some of the most lovable and life-affirming music ever composed.

##

Here is a complete performance of Haydn's Creation: