"What Doesn't Kill Us" (Linda Miller Raff)

An alternative version of this piece can be found at TheHistoryofTexas.com.

###

What Doesn't Kill Us

I live in a city that is full of magnificent, majestic oak trees, many of them hundreds of years old. History has been made beneath them— truces agreed upon, treaties signed, marriages made that spawned generations. Today, the long limbs of these trees span entire blocks and fill our parched pavements with cool pools of shade. I love these trees. I'm not entirely sure what my attraction for oak trees is— perhaps it's my wild and pagan Celtic heritage— but I have always regarded them as friends. Even as a child, I felt their wise spirits gazing down on me. And yes, before you ask, I have put my arms around a few and hugged them.

One of these local oak trees has a particular story that is international in scope but is so intensely personal that it might live closer to our community’s green-centric heart than others. It's a story that still makes the tellers and the listeners tear up a little. Many years ago, our city's most historic oak tree— called the Treaty Oak— was nearly destroyed by an unbalanced man who poured gallons of herbicide at its base in an act of romantic revenge. For centuries, this tree had survived the vicissitudes of nature, a war for independence, and the encroachment of civilization without incident. In ten minutes of its existence, the tree named to the American Forestry Association's Hall of Fame was almost utterly defeated by a single, random act.

As the news of Treaty Oak’s poisoning spread, arborists from around the country rushed here to begin triage. The diagnosis was grim. The aching people of my city gathered by the hundreds around its mighty trunk and prayed for this tree like it was a beloved relative. Hundreds of school children placed cards, candles, yellow ribbons, and notes near the tree in attempts to somehow urge it to survive. American Indians and healers of all types performed cleansing rituals. A national Treaty Oaks Task Force was organized. International media arrived. Rewards were posted.

We collectively willed the tree not to die. But it did. Mostly.

However, with the help of dedicated experts, 35% of the tree survived. The dead wood was cut away and made into commemorative souvenirs. The thinned-out, scraggly, lopsided tree hung in tenaciously, and eight years after its poisoning, Treaty Oak gave a grieved community a reason to rejoice. Acorns.

Today, the tree’s awkward reach is smaller, and its shade is less. But it is alive and giving birth to green leaves and generations of saplings. The fence around Treaty Oak prevents me from getting close enough to hug its slender trunk, but if I could get there, I would hug the heck out of it. And then I would tell this bent-but-unbowed tree thank you.

I don't know if I completely agree with the adage, "What doesn't kill us makes us stronger," because sometimes there really are things we just can't survive. And there are many other times when the crush of failure, hopelessness, and other assorted ills of life leave us prostrate and certain that this might finally be all we can take. But this damaged oak tree, still rooted in the soil and still reaching for the sky, reminds me that sometimes what doesn't kill us, just doesn't kill us. We may not be stronger, but reshaped and revised, we are still standing. And that is cause for grateful rejoicing.

© Linda Miller Raff

##

Related images:

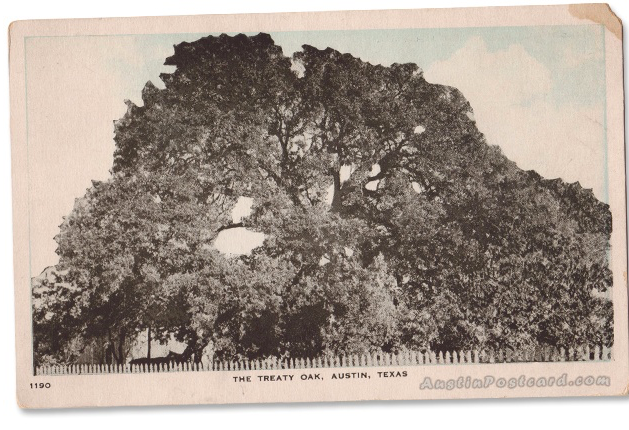

Historic Treaty Oak.

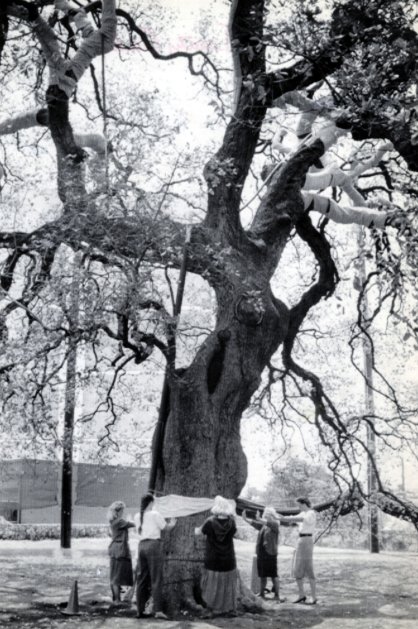

Treaty Oak around the time it was poisoned.

At the low point, circa 1990.

Treaty Oak circa 2017.

##

Linda Miller Raff is an outstanding education professional, writer, actress, and public speaker in Austin, TX. Also member of First Baptist Church. See more of her writings here.