A Block is a Watershed (Justin Stewart)

They say The West had a choice on how to develop our towns and jurisdictions in the late 1800s. City planning at the time on the east coast had generally been simple grids over each new city center, nice and predictable. Regional (county) planning was blockish as well. Grids are indifferent. We needed to spread west quickly and we needed a way to organize this immense amount of non fragmented Native American land. Manifest Destiny.

John Wesley Powell was one of our great explorers of the arid American West in the late 1800s. After witnessing the harsh and intense conditions of the southwest, he was positioned as the director of the United States Geological Service (USGS). From this post, he proposed that new jurisdictions and development be based on watersheds, versus the conventional plopping down of the Jeffersonian grid. He proposed that water be acknowledged as a resource, even a guiding principle in our urban and rural design.

John Wesley Powell on expedition of the arid west.

The powers that be kept with the grid, the largely arbitrary parameters were now set.

Austin, TX. is where my family calls home. It’s on the edge of the arid Southwest, arguably well into it at this point. We receive more than 75 percent of our annual 32 inches per year in just six rain events, big storms, when the sky opens up for hours and hours. New York City and Boston can get away with 3 inch street curbs to move stormwater, ours need to be at least 6 inches, even 10-12 inches in some areas. Further, giant infrastructure projects are implemented and maintained all through the southwest to move or temporarily store this big-event stormwater that would otherwise flood the grid. This is called centralized infrastructure; big, bold, expensive engineering feats to allow us everyday people the convenience to ignore how water moves through the areas we live, even our own houses. Centralized infrastructure can assure safety to the grid, and pardon the negligence of watershed planning.

Conversely, a rain garden is considered decentralized infrastructure. These little dry treatment ponds celebrate the idea of keeping rainwater (stormwater) closer to the land on to which it falls, repairing a small segment of watershed negligence. They improve the local ecology and potentially the community. Here is an example:

A friend of mine started a little community garden on a long narrow 9th Street lot in East Austin. For more than ten years, people have gathered, gardened, turned compost, played music and even held weddings in the public space.

The garden is in the middle of a city block, and marks the middle of a steep valley. The valley peaks at each end of the block, almost 25 feet in both directions. Water comes rushing down both sides and goes into an inlet, then flows in a culvert under the garden lot, past 1st Street and empties into Lady Bird Lake (The Colorado River).

This is still considered conventional stormwater management, pipe to pond. Or in this case it is pipe to river.

Of course the water didn’t always run off like this. Before the paved streets, back when this area of town was zoned for African Americans only, water simply ran down the unpaved streets, puddling where it may, rutting the steep road and finding the path of least resistance through the garden lot itself. So much water moved through this lot that it was deemed undevelopable and the city took ownership of it as a drainage easement. Fast forward through the 60’s, and past citywide underground stormwater infrastructure investments (gutters, inlets, curbs, culverts, outfalls, etc.), and the lot still remained vacant despite the stormwater now going under the lot to the Colorado River, versus through it.

My friend approached the city about turning the lot into a neighborhood asset, a community garden. With the help of long time residents, namely the recently deceased Julia Faye Mitchell (8/26/31-10/12/15), the city relinquished it for our use.

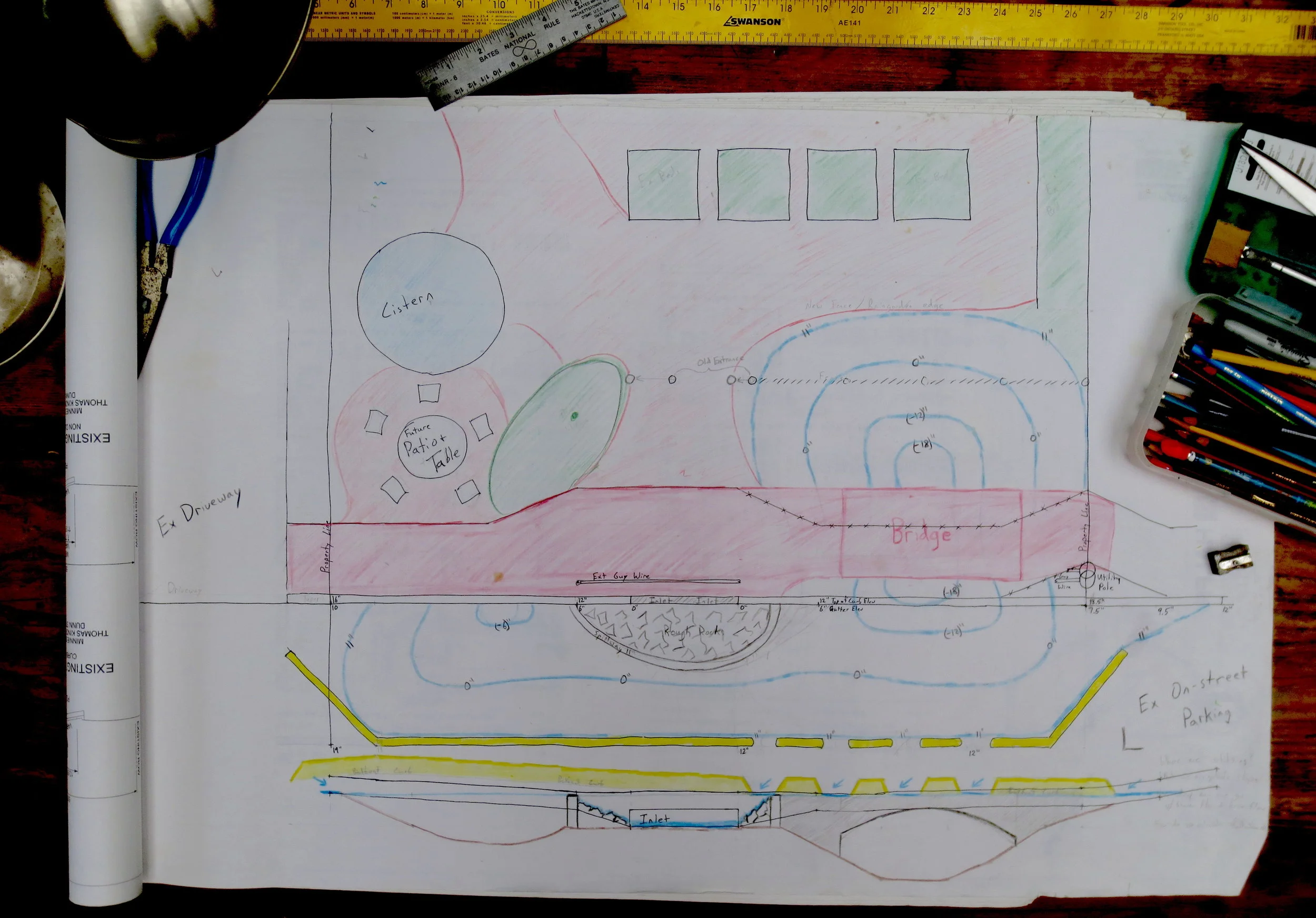

Then, not long ago, another ardent gardener friend and he had this notion to recapture and filter some of this stormwater before it raced downhill to the river. They sketched out a rain garden that could fit next to the inlet and it would cleverly serve as an entrance into the community garden itself.

As a founder and board member of Creek People, our nonprofit was happy to accept a request from this garden committee to sponsor this effort to harvest and return stormwater back to the garden soil in the form of a rain garden. We are now in the final engineering stage of creating a small pond that will intercept the “first flush”. Any additional runoff (from big rain events) would bypass directly to the gutter to avoid flooding. The first flush is important because it can carry up to 90% of the runoff pollutants from the driveways, yards and roads. Stormwater projects at the lot-level that slow, spread, and soak the water back into the ground are good examples of decentralized infrastructure.

The City of Austin fortunately has standards and regulations outlined in online manuals that have given us confidence to determine and calculate if a rain garden is indeed an appropriate stormwater solution for our situation. Does the soil drain quick enough (per Zika and West Nile concerns)? How big should the pond be? Who owns the land? Who would shovel out the trash and keep the new plants alive? How many pounds of pollutants per year would it remove? How big is the drainage area?

I was tasked with the last one, delineating the surface drainage area. Me and my trusted dog set out with a rough map my wife had made me. How big could it be? I was pleasantly surprised that the surface drainage for this one inlet was almost exactly one city block. It was also the very top of its larger Lady Bird Lake watershed, we were mapping the headwaters of an ancient stream. As the name suggests, headwaters are really special.

“How funny and convenient,” I thought, “John Wesley Powell would be amused at this coincidental agreement of a city block being a concise watershed.” It looked so simple to me. I was sure that I could show every person on this block the figure above and they would quickly understand where their water goes and why the quantity and quality is important.

It further inspired me to look at the building footprint of each lot that was contributing water to the single inlet. If/when we are to show our neighbors that they belong to this “special garden block watershed,” perhaps this “belonging” can be leveraged further. What if homeowners want to further contribute through holding (harvesting) their rooftop rainwater? What if some of them already are? What if some of them are excited, but can’t afford to implement a system? What if they are renters?

How many rooftops would we need to harvest, coupled with the rain garden, to achieve pre-development runoff? Could our team achieve this? We are working on it! If we succeed, how could we leverage our community and ecological service success to be replicated elsewhere when affordable? Would people from this watershed, these little hills in East Austin, give testimonials that could be used for positive social norming to influence future ecological restorations at the block level or neighborhood level?

That’s where we are on this project, navigating all the city permitting through a city-provided neighborhood partnership program to get the rain garden established, while also considering the potential of a block-level stormwater management of a coincidental block-watershed. Perhaps then we can find a local or state grant that could fund these decentralized rainwater harvesting systems. This is hopefully an example of how to harvest stormwater at the block level while improving the quality of life for the community.

##

###

Image credits:

"Wheelbarrow", "Compost", and "Arms-Crossed" photos by Laura Kennedy.

All other images by Justin Stewart.

Justin Stewart is a songwriter / environmentalist in Austin, TX. Visit JustinStewartMusic.com and CreekPeople.org for more of his great work. Justin's posts on AllCreation can be found here.